What have you touched with your hands today?

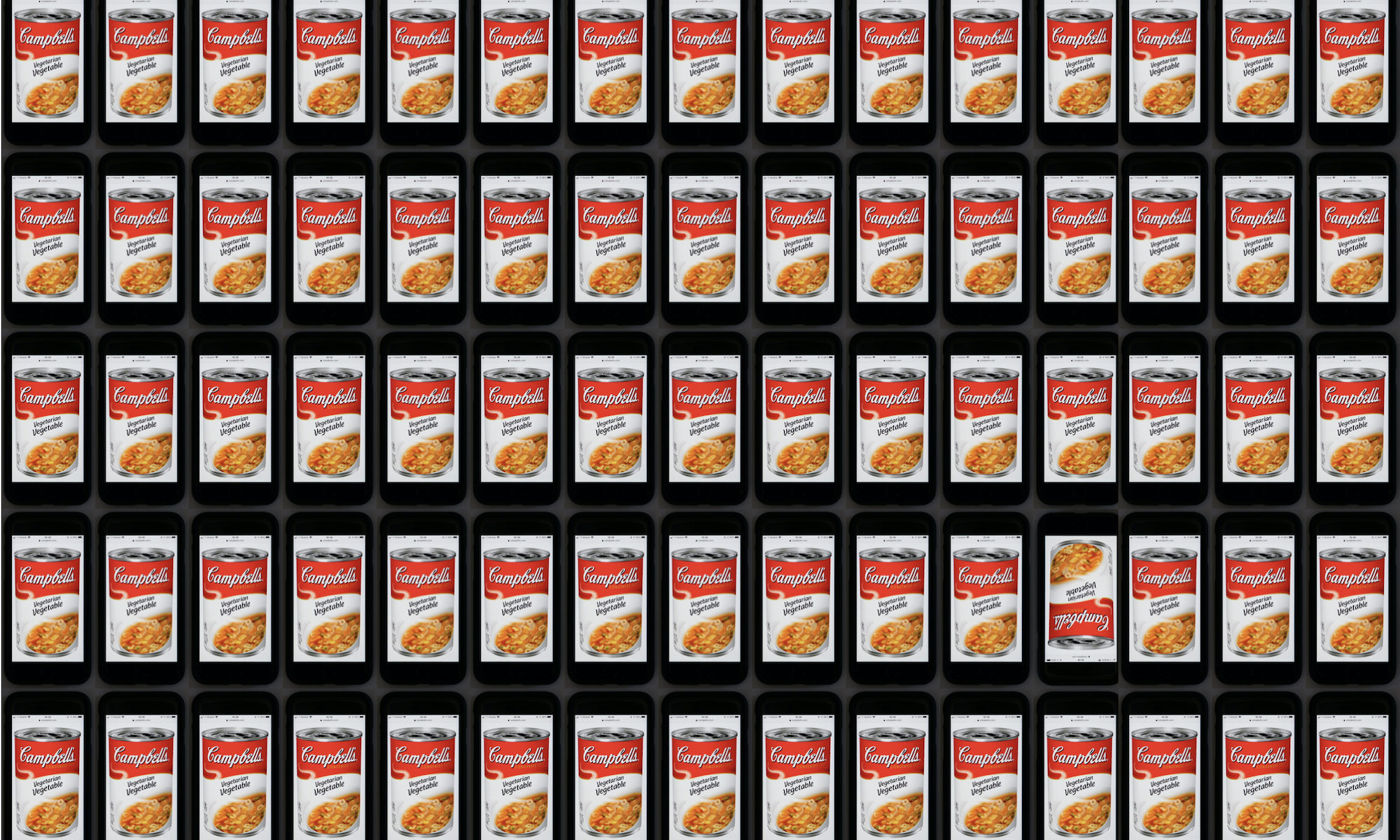

Your phone, your computer keyboard, your desk? What else? Do you even recall?

This morning: What do remember feeling, experiencing, touching?

Your hands: What textures did your hands encounter today? A surface that is scratchy, bumpy, unfamiliar? Or just the predictable smooth metal and glass of a gizmo, surfaces you touch to use but otherwise ignore? Did you notice any feeling in your fingers, or did you merely use your fingers to do things automatically, not focusing on your fingers and what they touched but on the tasks for which your fingers were the unacknowledged tools?

When did you last touch something made by nature, in its natural state?

When did you last bend to collect a pebble from the seashore or kneel to retrieve a fallen leaf on a hiking path? When last did the skin of your bare hand feel the texture, the temperature, the heaviness, the lightness of a tiny treasure?

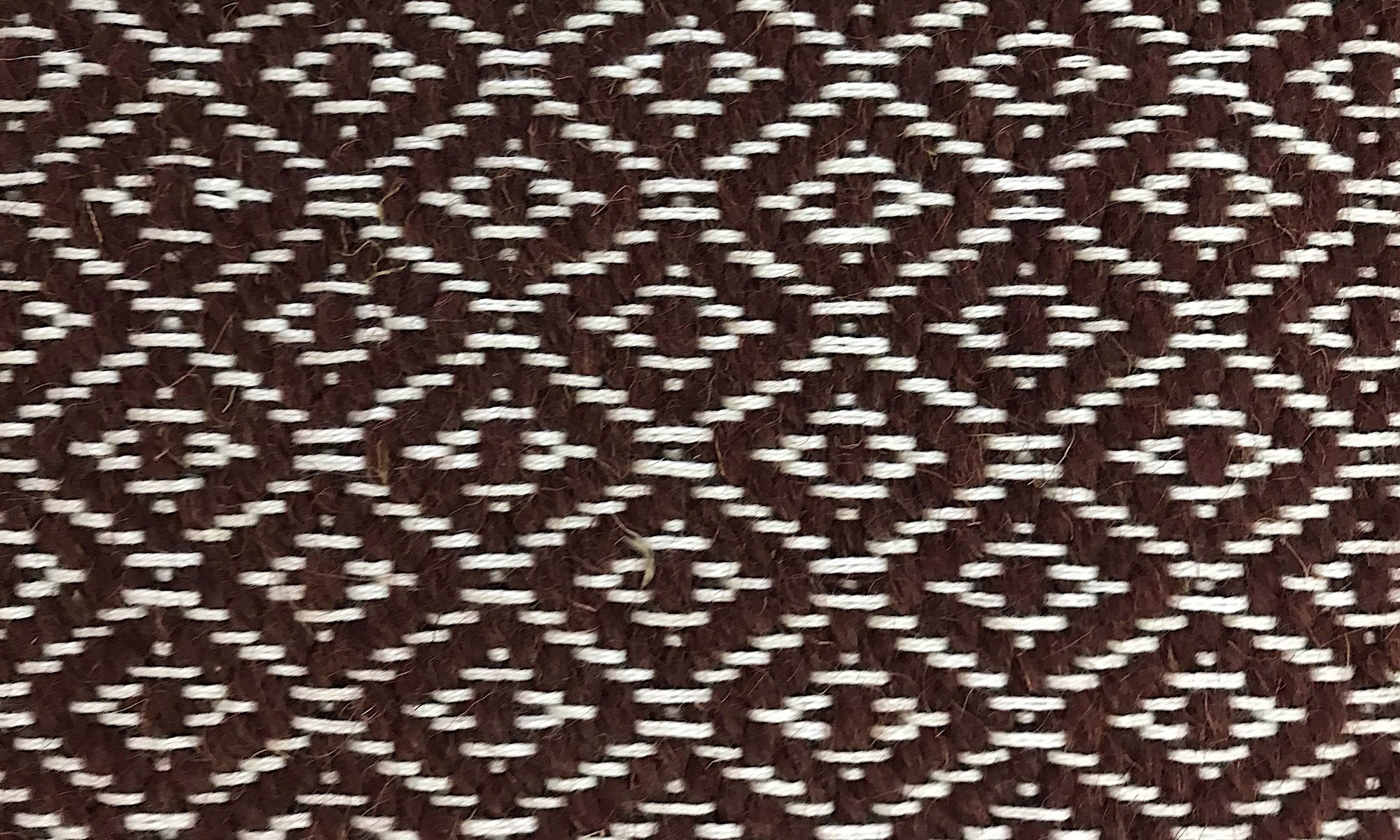

When did you last wear a woolen sweater knit by an aunt, and run your fingers over the rough strands of the yarn as you rolled the cuff? When did you last lean back on a wooden chair handmade by an artesian, and rub your palms on the armrests to feel the smoothness?

When did you last think about the hours and days it took to make such an item, contemplating the love and skill put into every stitch of the sweater and every sandpaper-swipe that went into polishing the chair?

When have you even thought of who — or what — made the items you use, the objects you touch each day, all day?

Most of us in today’s tech-focused Western world touch only machine-made items. We don’t generally think much about where or how they were made. The predictability and monotony of what we touch has made us callous (pun intended).

We’ve lost the sense of touch and the sensibility of touch. By dissociating ourselves from what we touch, we constrict ourselves and our world, ultimately disconnecting ourselves from what touches us. The world becomes senseless and spiritless.

Touch is human. We need to pay attention to what we touch, and we need to bring objects from nature and items crafted by loving human hands back into our everyday lives. More than needing objects — faster, sleeker, improved, enhanced objects — we need objects we can truly touch, and we need to be able to sense those objects on more than a superficial level.

Touching, feeling, and contemplating handmade and nature-created objects awakens our own sense of touch, expands our physical and emotional capacity to feel, and helps us connect with our individual and collective spirit.

Each of us and every thing carries an essence, a spirit. The ancients knew this, the mystics know this, and the artists know this. However, most of us forget that each thing and every person contains an essence — if we even knew this to forget it! Moreover, it’s easy to forget this when we forget how to touch. If we’re not aware the surface of what we touch, we can’t feel the deeper essence of what we touch. Everything we touch then seems flat, undifferentiated. We ourselves lose our dimensionality, our essence.

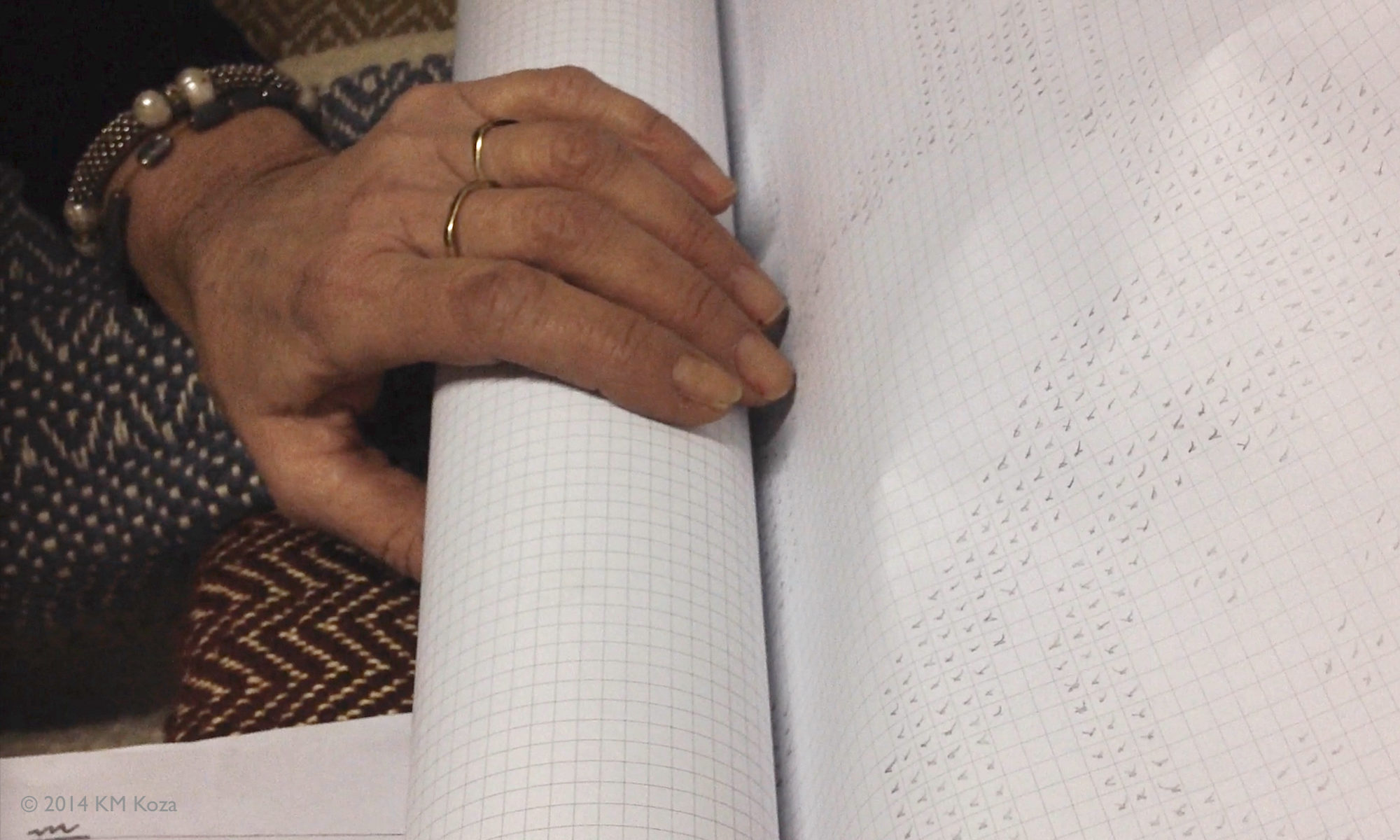

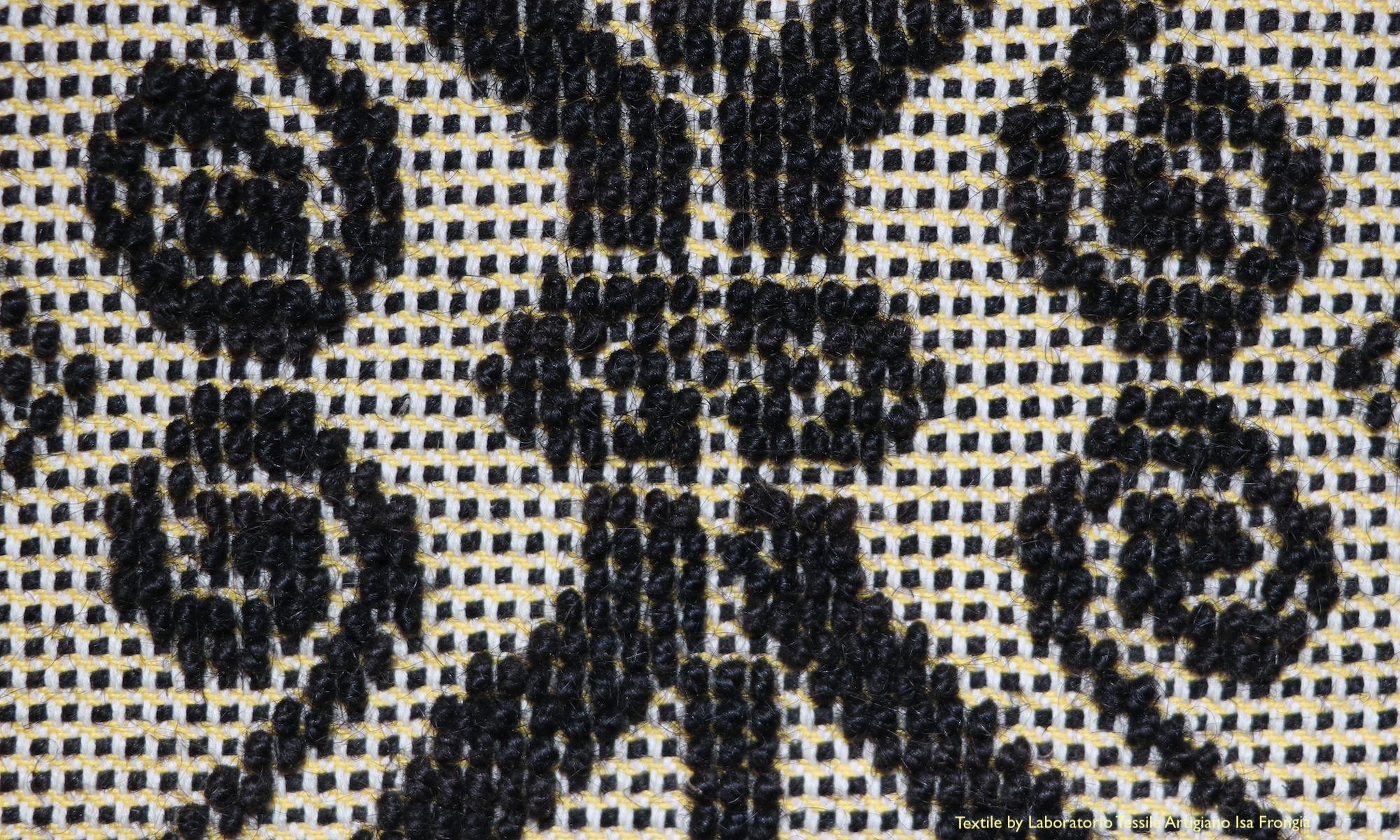

I have often suggested to friends that they keep a special rock, twig, or feather on their desk, and take breaks to consciously feel the item, or even to just hold the item when on calls and in meetings. Similarly, I suggest cultivating and actively using a collection of handmade items, including clothing, rugs, and pottery made by those we know or artisans from local or traditional cultures. These handmade items carry the essence of the maker: the care, consciousness, and love the maker has for their craft permeates each object they makes. This essence is tangible and it touches us — if we allow ourselves to feel it.

This essence of care, consciousness, and love is what we’re missing in the world today, whether we’re conscious of it or not. Making and using handmade items is a tangible way to bring some of this back.

©2021 KM Koza

This is cross-posted on SardinianArts.com.